The following article was published in the Sports Illustrated of October 12, 2015. It is reprinted here by the kind permission of those who not only commissioned the article, but helped with the logistics of getting Mike Epstein back to Washington so as to wash the sin from my hands. So, hey, when Judgment Day comes, they at least have this going for them. Thanks, guys.

* * *

THE STATIC of the broadcast, the AM-band crackle that the cheap transistor spit up every time it swung or bounced—even this I remember. Just as I recall the heat from the water in the hallway fountain, its cooling mechanism never quite functional. And the godawful smell of the secondary wing boys’ room.

It is 1971, and I am new to the fifth grade at Rock Creek Forest Elementary School, a few hundred yards north of the D.C. line in suburban Maryland, where everything is perfectly Proustian, perfectly preserved in memory.

I have been on the playground, playing strikeout with Firestone and Bjellos. It is an April afternoon, after school hours, yet unseasonably hot in my memory. I am wishing the water cooler actually worked, stumbling into the boys’ room to take a leak before drifting back to the game.

On my little Sanyo, Frank Howard launches a grand slam off the Oakland A’s starter, some fella with the improbable name of Blue. It is Opening Day. And though this is Washington Senators baseball, all things are still possible.

Two years earlier, in fact, my Nats, managed by the great Ted Williams, finished above the hated Yankees for the first time in my short life in a season when both played better than .500 ball. These guys are due. They have always been due. This, perhaps, is the year they pay out.

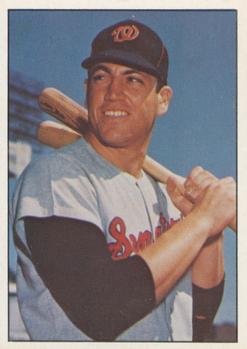

Mike Epstein follows Howard to the plate, and I rest the radio on the boys’ sink. Epstein, my favorite. Superjew—and yes, that is his actual nickname. Thirty home runs in ’69 hitting behind Howard, who had 48 jacks that year. And in ’70, Epstein added 20 more.

Is there a hero more tailored to my existence? Is it possible to overstate the sociocultural and psychological import of a power-hitting Hebrew playing first base for the Washington Senators, the hometown team of a skinny, slap-hitting Jewish runt from Silver Spring, Md.? Surely, Mike Epstein, standing astride my childhood like a colossus for all the Chosen, is a personalized gift from the god of my fathers. To whom I now pray:

“Dear God,” I offer aloud, my words echoing against the drab brown walls of the bathroom. “If you let Mike Epstein hit a home run right now, I will never, ever skip Hebrew school again.”

Whereupon the very next pitch is launched into the rightfield upper deck of Robert F. Kennedy Stadium. Back-to-back with Howard. The Opening Day crowd cheering wildly because maybe, just maybe, this is the year, with the Nats embarrassing this Blue fella and shutting out Oakland to begin the great exodus from Egypt and bondage.

And here, now, comes the worst and most frightening image in this sequence of memory: That of a mop-headed boychild, arms above him, cheering wildly, his image reflected back from the old oxidized mirror above the school bathroom sink. I can still see that fool kid. Right now, in my mind’s eye, I am looking at him as his moment of delirious joy evaporates into near Biblical loathing and terror.

What did I just promise God?

Oh.

No.

* * *

I’M NOT AN IDIOT, or a fundamentalist. A sentient grown-up cannot take seriously the notion of petitional prayer in any sporting contest. Any modernist knows that a divine entity who would intervene in human affairs to hang a curveball or block a field goal is a deity with too much time on His hands. Any god who actually exists has to be playing for larger stakes than a playoff win or, worse, a five-year contract with built-in incentives. The sight of a wide receiver falling to one knee and crossing himself in the end zone is an affront to any theology that can matter. And we must concede that a serious god in whom real purposes abide cannot possibly give himself over to punishing the random collective of northside Chicago baseball enthusiasts merely because they don’t live in St. Louis.

So, O.K., no worries. I made a vow and I broke it. Within three weeks I was again cutting out of Hebrew school on Tuesday and Thursday afternoons, hanging with friends, creeping down Beach Drive to play basketball in Rock Creek Park. But so what?

God, if He even exists, is good, or at least noninterventionist—an Unmoved Mover, as Aristotle would say, who rules from a heaven with high walls and leaves small matters of athleticism to men. A child’s vow over such nonsense is unheard.

Except a little more than a month after that long-ago Opening Day, Mike Epstein, my favorite player, was traded to the Athletics. And by the following season my entire hometown baseball franchise, the Senators, was shipped to Texas to become the Rangers.

I did the rest of my growing up in Washington without baseball. And when I moved to Baltimore in late 1983, I could in no way enjoy the Orioles’ victory in the World Series that year. The O’s of old were Canaanites, a savage crew of Moloch-worshippers who routinely marched south against my tribe, with the Robinsons and Palmer and McNally and Boog smiting and martyring the Nats at will.

I rooted for Philly in that Series, and only embraced the Orioles when they began the ’88 season with 21 straight losses. As only a Senators fan will, I came to my second franchise when it was in the basement, and for a long time the elevator did not move.

So note:

It is now nearly half a century since a small boy asked his god to hang a Vida Blue pitch for his hero, and neither team with which he has allied himself has to this moment returned to a World Series.

Lo, the Orioles have wandered like Israelites through Sinai since I took a mortgage in Baltimore, teased from New York by Jeffrey Maier’s mitt and mocked from Chicago by Jake Arrieta’s fastball. And the new Nats, reconstituted a decade ago, have touched the hem of greatness only to collapse at the very edge of every playoff opportunity. They ended the present season, literally, at each others’ throats.

My vow, I have come to believe, was heard. And now I am Jonah, fleeing from my God and Nineveh, unwilling to address my sin. And the Nationals and the Orioles are both ships on a storm-tossed sea, their sickened, seasick fans unwitting victims of the outcast who walks among them.

Every season since 1971, the gaping maw of the whale awaits me. I am to be swallowed, along with the hopes of any baseball team I care about, into the belly of the beast and spit up in time to do it all again when pitchers and catchers report.

I gotta get right with God.

* * *

NEVER HAPPENED,” says Mike Epstein.

The phone line goes silent.

“No way,” he adds.

Finally, I say something clever: “What?”

“I never hit a home run off Vida Blue, and I never hit a home run on Opening Day. You got it wrong.”

“But I remember it.”

“Never happened,” he repeats.

I sit there on the other end of the phone, stunned like a cow with a sledgehammer. Me. In the boys’ bathroom mirror. My promise. My sin.

“Listen,” Epstein says finally. “You’re not serious about this, are you? Because, I gotta just say, you realize this whole thing is a bit, ah, egocentric.”

You think? Isn’t everything that constitutes the theology of fandom egocentric? Believers who won’t change their shirts for 16 Sundays if their team is winning? Acolytes who have to walk out of the room on a full count with loaded bases because if they stare at the television screen, the Fates will bring bad juju to the moment? Pilgrims who eat the same thing in the same inning in the same number of bites because the ritual assures the outcome?

Surely a direct appeal to Yahweh, the god of our forefathers, carries more gravitas than mere fate?

And no, I still don’t believe a just god intervenes in professional sports. He does not care if Mike Epstein goes deep against Vida Blue, or whoever threw that pitch on whatever day he threw it. But does He care if a Jewish kid two years shy of his bar mitzvah promises to stop cutting out on Hebrew school?

Think on that for a moment, Mr. Epstein. Maybe this vow wasn’t about baseball. Maybe it was about theology and spirituality and the 6,000-year-old faith of our ancestors.

“You’re serious,” Epstein says wearily.

“You and me, we gotta bury this together.”

And somehow, I get this man to agree. Somehow, I convince him that the two of us hold the future of the Nationals, and possibly the Orioles as well, in our sin-stained hands.

He will come east from his home outside Denver, back to Washington. We will taste the bread of affliction together, share a Passover seder and use the Jewish holiday of liberation to commemorate the long years of wandering in baseball wilderness, to dream anew on a Promised Land flowing with milk, honey and freshly printed playoff tickets. Then, on Opening Day of the 2005 season, we will go to the old RFK Stadium, where the Montreal Expos have just relocated, and we will watch a ball game together.

I know I have Mike Epstein aboard when I can hear him laughing at me through the telephone.

“O.K.,” he says. “You’re nuts, but O.K.”

All that is left for me, other than buying his plane tickets and reserving a hotel room, is to figure out my broken memory. Back-to-back home runs with Howard. Vida Blue. Opening Day. The upper-wing boys’ room at Rock Creek Forest Elementary.

“I’ll work on that,” I tell my childhood hero. “And I’ll see you next April for Passover.”

Except the Old Testament god, He is not so easily appeased.

A few months before Passover in 2005, my brother-in-law, a sailing enthusiast, was caught in a storm off the Florida coast and, when a metal coupling fell from the mast, suffered an injury that would eventually prove fatal. That year’s family gathering was no time to trifle with anything as obscure as baseball voodoo. And by the following season, my father had become invalided; our Passover seders became, for several years, private affairs. I couldn’t follow through with Epstein.

Season followed season. The Orioles slowly improved and made a couple decent runs toward a Series, but last year’s rollover to Kansas City seemed like a high wall. The Nats, for their part, looked weak-willed the year they sat Strasburg, and last season’s playoff performance was so devoid of heart that some supernatural element could be plausibly suspected. In the back of my mind, totaling up the cumulative seasons of Series- less baseball in my wake, I piled up a weight of guilt that only Jews and Roman Catholics can carry.

Verily, my God was still an angry God. So, a decade after I first contacted Mike Epstein, I called him again. He didn’t return the message. Not right away. Who calls a goof like me back a second time in a single life?

I had an editor from Sports Illustrated follow up, if only to make my pitch more plausible. And I called the Nationals’ front office, asking about the possibility of honoring one of Washington’s former baseball stars. And in July I flew to Denver, where, finally, seated across from an aging but still athletic man, in a breakfast spot south of the city, I did all I could to assure my boyhood hero of both my sincerity and my sanity. I also told him I had solved the false manufacture of memory, and it was a telling corruption at that:

“When you make a promise to God, a promise that you don’t keep, a promise that you then secretly blame for the trade of your favorite player and then the loss of your entire baseball team, well, you kind of want the home run to matter. And for the Senators, the only way a home run could matter was to have it as close to Opening Day as possible because by May….”

“By April, you mean,” laughed Epstein, remembering. “Those teams were so bad.”

“By April,” I agreed, “the Washington Senators were usually out of contention.”

Mike Epstein and Frank Howard hit back-to-back home runs on Aug. 17, 1970, in the first inning of a 7-0 home win over the Kansas City Royals, off a pitcher named Bob Johnson.

It was summer. A hot day in D.C. My fifth-grade year hadn’t started yet, but the school building would have been open as the staff was preparing for the start of school. In August, we were routinely allowed to use the bathrooms while we hung on the blacktop and played ball. That explained why my memory had no one else in the hallway or bathroom, why I was even allowed to have a transistor radio in school that day.

Ridiculously, I had offered up a vow to God over a single at bat in the first inning of a late-season game for a sixth-place team that was last in the old American League East — that was in no way contending for anything. Not even pride. Biblically, this is the equivalent of Esau trading his birthright to his brother for a bowl of soup. Yet over the years, as the baseball fortunes of two cities fell and as I bricked a personal prison cell using mortared blocks of Judaic guilt, I imbued that useless home run with more and more meaning.

The Senators had in fact shut out the A’s on Opening Day in 1971, beating Blue in the same convincing fashion that they had shut out Johnson and the Royals. That, too, was a warm memory, one that I happily conflated with Epstein’s prayed-for homer if for no other reason than to make my plea for divine intervention more purposed and romantic.

“Do you remember what pitch you hit off Johnson?”

Epstein had some memorable dingers in his career. Three in one game. Four in consecutive at bats. And some astonishing artillery salvos to the upper deck of RFK, where they painted the seats blue in Superjew’s honor. But an August home run in a game that meant nothing?

Epstein didn’t remember the at bat, much less the pitch on which he turned.

Only I did. Kinda

* * *

NEVER MEET your heroes, it has been famously said, and as an old newspaperman, I’ve generally been inclined to credit the adage. A hero is someone far enough away so as not to reveal himself completely.

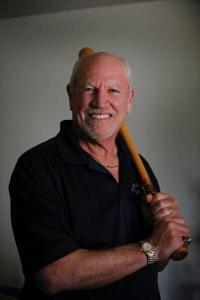

But the Michael Peter Epstein who has put up with my on-again, off-again courtship these many years, upon our first meeting in Denver, revealed himself to be a fine, if somewhat skeptical, soul.

A professional ballplayer from 1964 until he retired 10 years later—just before the rise of free agency and a seller’s market—Epstein was obliged to turn on a dime and embark on a second career as a businessman.

A native of the Bronx, he nonetheless learned about the cattle market, of all things, and would own and operate ranches in Oregon and Wyoming. It is probably safe to say that in meeting the man, you are shaking hands with the only lefthanded Jewish power-hitting cattleman to ever stride this planet.

And for a third act, Epstein returned to the baseball world, developing batting techniques and drills that he describes as rotational hitting—an influential and level-swinging counter-revolution to the Lau-Hriniak school that dominated the game a couple generations ago.

Asked the ageless Talmudic question—”Which is harder: hitting or preventing hitting?”—Epstein doesn’t hesitate before offering his own rabbinical dissent: “Teaching hitting. That’s the hardest.”

It was not something that he particularly wanted to do in life, but when the greatest hitter in modern baseball history prods and pushes repeatedly, you eventually give way. And Ted Williams, having managed Epstein for two-plus seasons with the Senators, had kept a friendship with his former player.

Williams knew hitting as a precise science, of course, but teaching it? He had no patience or vocabulary for explaining himself or his skill. But he would talk hitting with Epstein.

“You gotta do this,” Williams told him on one hunting trip together.

“Why me?”

“Because you’re a smart sonofabitch. I can do it, but you can figure out how to explain it.”

Beginning with a series of 42 articles in the Collegiate Baseball Newspaper in the early 2000s, Epstein codified what Williams believed about smacking a baseball with a bat into a coherent, teachable methodology. Today, Epstein Online Hitting Academy—now a second-generation enterprise with Mike’s son, Jake, at the helm—has become an influential font of batting analysis and coaching, based in Littleton, Colo., with 650 certified instructors operating nationally. It is the only hitting curriculum Ted Williams ever endorsed.

For Epstein—successful as a player, as a cattleman and businessman, as a hitting guru—life has been a series of pragmatic, goal-oriented paths and pivots. You show up, you do the work, you wait on the proper result. Stray prayers and divine interventions are not currencies in which such a man generally traffics.

* * *

BUT THE OLD TESTAMENT God, the jealous God, the unforgiving God of some improbably chosen tribe of ancient desert wanderers—maybe He’s not interested in your modernist sensibilities, or in your hard-won rationalism. Maybe He’s keeping different stats on this world, and judging mortals by different sabermetrics altogether. And maybe this God is not in the business of cheap forgiveness, either.

Because this ball season, on Sept. 21, the night before Yom Kippur, the sundown commencement of the Jewish Day of Atonement, I arrange to bring Mike Epstein—who remains politely dubious about the entire enterprise—to a stadium in the city of Washington, where the third and present incarnation of professional baseball in D.C. resides. There, just a mile or two down the Anacostia riverbank from the hollowed-out hulk in which Epstein once played, we stand in the Nationals dugout, waiting out a rain delay.

“God,” Epstein assures me, staring at the infield tarp, “is really angry at you.”

It’s an hour past the game’s scheduled start, and Epstein, having done all his interviews for local radio and pregame broadcasts, stands with a team escort at his side. In the escort’s hand are a Nationals jersey with Epstein’s name and number 6 adorning it, and a red ballcap with NATIONALS spelled out phonetically in Hebrew letters. But the rain is unrelenting, and there will be no pregame honorifics for Epstein or anyone else. In the end, a little after 9 p.m., this Monday game between the Nats and the Orioles—yes, my plan was to exorcise the demons from both franchises at once—is called for weather. It will be rescheduled as part of a Thursday doubleheader, a day which will find Epstein back in Colorado.

God will have no apologies from me.

Yea, as it shall ever be written: Man plans, grabs a bat and walks to the plate. God plunks him in the ribs with a nasty slider, and then, two pitches later, picks him off with an omnipotent little move toward first.

* * *

To my right, my sister-in-law, Vicki, and brother, Gary; to my left, Mike Epstein, walking to Kol Nidre service on Yom Kippur this year in suburban Washington.

AT SUNDOWN the next day, Mike Epstein and I find ourselves at Har Shalom Synagogue in the Potomac suburbs of Washington. We are side by side as the congregation rises for the Kol Nidre, the All Vows prayer, in which Jews ask God to forgive them for all of the promises that they, being human and foolish and fallible, will fail to honor in the coming year. Kol Nidre is so elemental to the Jewish ritual of forgiveness that we chant the prayer thrice, slowly, so that the words are given all possible attention and clarity.

As I gather my prayer shawl on my shoulders and turn the page of my prayer book, Epstein shoots me a look and actually smiles. “O.K., you’re up,” he says. “It’s on you now.”

Kol Nidre applies to the unkept vows of the coming year, but I’m asking for a retroactive dispensation. My great sin dates to my 10th year of life, and I know I didn’t even learn the Yom Kippur liturgy until I was 12 or 13. Hey, with all those unexplained absences, I wasn’t the brightest bulb in the Solomon Schechter Hebrew Academy. Sue me.

Yet on this night, I bend to the task. Beside me, I can hear my companion muttering the Hebrew as well; neither of us is particularly observant, but Epstein too has knowledge of the liturgy. But walking out of temple an hour and a half later, he only partially concedes the validity of our mission together:

“I get why you’re here, but explain to me exactly why I had to make this trip? I did my job. I hit a home run. And God, he did his job, right? You’re the only one here who still owes.”

I do my best:

“You’re part of the sin, too,” I say. “I prayed for a home run in a meaningless August ball game, and I got it. But maybe you got something too. Maybe you benefited from the sin.”

He looks at me, ever more dubious.

“Look,” I say, “that year you hit 20 home runs, and early the next season you get traded to Oakland to play on a winning team. The year after that, you win a World Series, right?”

He nods.

“Maybe if you finish 1970 with only 19 home runs, maybe that’s not such a clean, round number. Maybe when the Oakland front office is looking around for a lefty to hit behind Reggie Jackson and play first base, maybe they don’t bite on Mike Epstein. Maybe if I don’t ask God to have that Royals pitcher hang a curveball, you don’t get traded, you don’t hit 26 jacks in ’72 and go to the World Series and get a ring.”

Epstein considers my theories on man and fate for only a moment.

“Weak. Very weak,” he says, laughing.

I drop him at his hotel and we say our goodbyes. And then, before getting back in my car, I shoot a look up at the dark Washington sky.

“C’mon, big guy,” I actually say aloud. “What’s done is done. Let my people go.”

At that moment, the O’s 2015 wild-card run is history, and with some irony, their last series with the Nats will fire the last torpedo into Washington’s hopes as well. But next year might be different. I tell this to myself and drive home with hope in my heart.

Five days later, the Nationals’ closer tries to choke the team’s best hitter in the dugout, for all the world to see.

Oh, God.

* * *

- 420shares

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

I think you are right about the 20 home runs instead of 19 being a key factor . That is funny he didnt really understand how you were most likely the reason he was traded and got a ring. It does sound ridiculous, but I understand that you might have made it happen. It could be the Mandela effect too? LOL. Maybe other people remember what you remember? Or maybe there needed to be a way to connect The Wire to Oakland. I just watched We Run This City and noticed you guys were talking about Batts. He was in Oakland before Baltimore. I think you portrayed him correctly LOL . I didnt know he was on the way to another country, that is funny. That is how he left Oakland. He came here after the 4 police got shot in 2009 and was gone by 2011. I am starting to think / already have thought for a while that there are no coincidences . Have you ever thought about writing a story about Oakland, California? Because if you dont I might have to, and I am not that good at writing LOL. I have read Homicide , The Corner and have watched The Wire so many times I cant even count. It shows up everywhere in my life. I was painting a green scooter black the other day because it was so ugly being green, and having registration that is not current I decided I should make it stand out a little less. As I was painting it, I noticed it was red underneath. First it goes to red, then it goes to green then it goes to black I thought. SMH. I looked on your twitter the other day and you said something about a lima bean . Just a few minutes PRIOR to reading that, I was cussing at a Lima Bean, it was the first time in my life I had done so, that I can remember. I was unthawing some frozen mixed beans for the fried rice I was making and the lima bean fell into the sink where I tried to recover it but was up against the blade of a knife , I still tried, and the knife almost got me , then I cussed at the lima bean . Like “gd lima bean mf wtf I dont need this shit , tryna cut my ass for a gd lima bean, mfer” . I realized it was a little ridiculous at the time but everything is I just thought, fuck it, its 2022 , lima beans are getting cussed out . When I saw you mentioned a lima bean, I just didnt know what to think anymore … Maybe I should start writing? I did a little. I guess this counts? Probably not. Well I guess any sequence of words typed by an Oakland CA resident that is longer than a craigslist ad should be applauded … I finally spelled applauded correctly after a good back and forth battle with the red underline . I think my work is done here. What is a slogan for visiting Oakland? I just looked it up, Its, Love Life … haha 4sho I should have known that , it is on the Welcome to Oakland signs , a whole nother story . Your favorite player got to play for the 1972 championship Oakland A’s where he hit a career high of 26 HRs and got a ring. I would bet that God probably already knew you were still going to skip class .

I am Angela, a senior at Immaculata University, a small Roman Catholic university Northwest of Philadelphia. I am a mother and student. One of the courses I am currently enrolled in is Baseball in Literature. We have read numerous novels relating to baseball and the history of the great sport. We have also had guest lecturers who were inspiring and very knowledgeable in regards to baseball as well. We even held a mini-clinic where we learned how to bunt and the art of fielding. Professor John Church, has stressed to us how important baseball truly is and how it is not ‘just a sport.’ There are many ways someone can use baseball as a way to get to God, and I see how you referenced that throughout your article. Baseball is a sport that brings about community and it is also a symbol of one of America’s oldest pastimes. After reading your article, I found most interesting that you had a great deal of nostalgia in your article. You recalled details, such as back when you were in elementary school and playing baseball. This reminds me of Doris Kears Goodwin, the author of the novel Wait Till Next Year. Goodwin focuses on her early life and how baseball was a very important part of growing up and her relationship with her father. One of the reasons I found your article so interesting is because not only did you bring up old memories from your early life, but the many details you can recall with each memory is outstanding. I am not a pro at baseball, nor do I even really watch it; however, your article was easy to read and it helped me to recall early memories that I have had in other sports that I used to play as a little girl.

My favorite part of your article is the way you structured it. It made me want to keep reading. You explain how you felt physically and emotionally during times throughout the game. “’Dear God, I offer aloud, my words echoing against the drab brown walls of the bathroom. If you let Mike Epstein hit a home run right now, I will never, ever skip Hebrew school again.’” I love how you display your anxiousness in such a humorous but also real way. It is very real and I could relate in a different way. I could sense your excitement and readiness for the next pitch to be thrown. Another feature of your piece of writing that I enjoyed is the overall aspect that you referred to God many times. I find it fascinating when someone brings baseball and God together because I, not so much a baseball fan, did not see how they could relate to one another until this class and hearing from different speakers how God and baseball are related in their own lives. For example, Mike Sielski, a commentator for the Reading Phills, came to speak to my class. He explains how baseball was the tie he had with his son while the family was facing difficult times relating to his son’s health. In regards to your article and God, I particularly found the part where you mention, “When you make a promise to God, a promise that you don’t keep, a promise that you then secretly blame for the trade of your favorite player and then the loss of your entire baseball team, well, you kind of want the home run to matter” to stand out to me. It shows how much you relate God to your life and you bring about a topic that I know I have dealt with before and I am sure other people have as well: asking God to help you with a miracle, and saying to him that you will do something great in return if he helps you out.

Overall, I truly enjoyed your article. I hope my feedback serves you well and I look forward to reading many more articles of yours.

I’m not Jewish, but I, too worshipped at the altar of Epstein. Thank you for writing so eloquently on the subject of our secondary (if not primary) religion.

[…] The frauds of memory, the limits of penitence. And baseball. […]

Wow! This reminded me of my Jewish connection to baseball. My brother Allen and I were kicked out of Hebrew School on our first day, because we were playing catch with our Yamulkas. My first baseball hero was Hank Greenberg along with thousands of other kids who happened to be Jewish. When I was 8 in August 1945,on my return from Summer Camp Henry Horner(named after Illinois first Jewish Governor) my Dad gave me a crash course in Baseball 101,Cubs history and a special chapter on Hank Greenberg. Then he took me to my first game at beautiful Wrigley Field. When the Cubs clinched the N.L.Pennant, I asked him to take me to the Tigers/Cubs World Series. He felt I was too young,however he made me a PROMISE-he would take me the next time the Cubs make it there! In 1947,he took my brother Allen and me to the Cubs Opener. I had mixed emotions when Hank Greenberg,playing for the Pirates in his first N.L.game hit a 2 out double in the 6th inning driving in the games only run.

In 1948,when Greenberg was the G.M. of the Indians, I sent him a mezuzah before the season started. He sent me an autographed picture. That year the Indians won the World Series and I figured it must of happened because I sent the good luck charm to Hank!

In 1950, I sent another letter to Hank,complaining about Yankee Manager Casey Stengle who left Al Rosen off the All-Star game roster who came in 2nd to George Kell for starting 3rd baseman with Gill McDougal who came in 3rd in fan voting to replace Kell who was on the D.L. Greenberg wrote back, that Rosen was young, and he will get many more opportunities to play in future A-S games. Hank was right, in ’54 Rosen started, and hit 2 homers and drove in 5 runs! (sadly I did not keep the letter in a safe place and it was lost when we moved) What I later found out… that once Greenberg was left off the A.L. All-Star Roster even though he had 100 RBI’s at the All-Star break. However the 2 guys that made it was Jimmy Foxx and Lou Gehrig!

In 1951, I remember listening to the Game of the Week on the radio and recall a very unusual circumstance. It was a game between the Tigers and the Indians. Saul Rogovin was pitching for the Tigers(he won the ERA Award that year) and his catcher was Joe Ginsberg. And Al Rosen was the batter and it might of been the first time 3 Jewish players were involved with an at bat in MLB history.

In 1954, I wrote a letter to the Cubs asking them why they did not have any Jewish players… and their letter back to me is a classic(I would of attached if it was possible).

In 1981, I got to meet Greenberg when he came to San Francisco to dedicate a couple of grandstand seats from Tiger Stadium at a local S.F. bar owned by Tiger fan. I told Hank I was at his first N.L. game,and I leaned something I did not know… that his 57 homer in the year he was chasing Ruth’s record was an inside the park homer. I also got to meet Rosen when he was G.M. of the Giants.

Of course i remember Epstein, and almost every Jewish player since who made it to the majors. I also realize that you didn’t have to be Jewish to root for Greenberg anymore then you had to be Italian to cheer for DiMaggio,or Polish to cheer Musial or black to root for Jackie Robinson, but it’s always nice to have something in common with your heroes!

‘Crossing yourself’ is never ‘an affront.’ You should be ashamed of writing that.

Thanking god for an athletic triumph is an affront to a just and caring god of all creatures. If he gave you the HR, then he hath forsaken the gopher-throwing pitcher. And worse, a god who intervenes in such small affairs as this has so much to answer for that he becomes deserving of our lasting contempt. The same diety who intervenes to block a field goal in a high-school game has failed to intervene to save some kid from leukemia? Really?

Sorry. Can’t muster shame for saying the public displays of faith in regard to athletic outcomes leave me ice cold.

Christians who pray ostentatiously when they know millions of people are watching them ignore Jesus’ words in Matthew 6:5

“When you pray, you are not to be like the hypocrites; for they love to stand and pray in the synagogues and on the street corners so that they may be seen by men. Truly I say to you, they have their reward in full. “But you, when you pray, go into your inner room, close your door and pray to your Father who is in secret, and your Father who sees what is done in secret will reward you.…”

Many Christians say that this passage does not mean what it says, and that Jesus did not intend to prohibit all public prayer, but only those prayers done for public approval. But even if that were true, it’s hard to imagine a person having a private moment with God in front of a stadium of 55,000 fans and millions watching on TV.

They do it because they know it makes them look good in the eyes of many, and that it hypocritical.

I wouldn’t presume to use a given religious text to argue circularly against a given sect’s religious practice. My argument is more philosophical than theological:

1) If you think your god aided you in a contest against another athlete, you are saying the same god exerted against another of his beloved creations who opposed you, implying that said opponent was somehow less deserving of a winning outcome. This is an affront to the dignity of athletic contest and the purposes that underly such. It is, in a phrase, bad sportsmanship.

2) If you think that god is so open to being petitioned for outcomes that he is connected in any remote way to whether, say, a wide receiver holds on to a touchdown pass or a referee fails to call holding on the same play, then of course that same diety ought to be available to prevent every cancer diagnosis or plane crash or grevious misuse of a human life whenever people are ready to fall to one knee and thank god for it. And of course He or She clearly isn’t intervening in human affairs at such an elemental level. Ergo, if god is busy using his omnipotence to assure that, say, the Mets pull off a double-steal to score the tying run in an eighth-inning rally at the same moment that, say, a bus plunges over the side of a Chilean ravine, then, well, god is really kind of an asshole. Sorry.

God really is some kind of an asshole.

As a Cubs fan, I can tell you this without any fear of (further) reprisal beyond a one or two more centuries of losing. How? Well, worse than being an angry god, he’s an apathetic one. Ask any Yankee fan: it’s much better to be hated than ignored.

The Cub’s god doesn’t get angry, he just gets busy with other things. He no longer helps with the scouting, he won’t involve himself with the management or even the mascot, and despite having the best seats in the park he refuses even to make an appearance at the night games. Word around the campfire is that he’s become a Blackhawks fan since they started broadcasting the home games on cable–which works out well, as he’s become something of a recluse. To paraphrase an old song, he don’t get around much anymore. Call him and you get a busy signal if you’re lucky.

So what’s he busy with? Well, there’s a war on Christmas that has been a PR nightmare and just will not go away. On a related note, there’s a decreasing ticket sales across the majors: churches, synagogues and mosques, as well as a the minors: bingo halls, bake sales and bottle drives. Worse, sales of his books, cds, and collectibles are way down (If you’re looking for some Christian-Bale-Moses bobbleheads, I know a guy who knows a guy). In short, he’s having a crisis of faith. He’s lost as much confidence in himself as people have in him, and as millions have come to doubt him, he’s come to doubt himself right into non-existence. He’s become such a recluse he makes Citizen Kane look like a Kardashian. The downside is that we can’t cut deals with him any more (or any less–as we never could), but the upside is that we can be satisfied relying on the best efforts of those athletes and teams we enjoy and respect to win or lose according to their own efforts and limitations. They may not win every game or every season, but they will play according to their own abilities and free will and there is some small victory in that.

This is an amazing, intelligent response. As a Cub fan I am in total agreement!?

A man! I love your response… I also hate when a pitcher wins a game and then points his finger toward the sky… like God has been watching the whole game and rewarded him for doing what he is paid to do!

[…] Simon’s The frauds of memory brings together baseball and Jewish holidays, leading to a beautiful and effecting read (orig. […]

Rock Creek Forest – class of ’62. Later arrived a Danny Bjellos, who either moved into the area or came from another elementary. He was a good athlete and a running back @ BCC. I heard somewhere that Epstein’s career was compromised by his refusal to wear glasses or get contacs. Attended Hebrew School @ Ohr Kodesh (which was then MCJC). Gave my Hebrew School teacher the finger (which I thought he had no chance of knowing what it meant) and was sent to the office. They called my parents. As I recall it, my pappy said “Son you’re gonna drive me to drinkin if you don’t stop drivin that hot rod Lincoln.” Though, again, my memory may be playing tricks on me.

What a great piece, David… I am sure I made similar promises when I was a child… more likely in September of 71, when the Senators were leaving. I actually went to opening day in 71.

Fantastic, funny piece — with the added nostalgia of our old neighborhood. But I figured you went to Hebrew school at Ohr Kodesh, no?

Ladies and Gentlemen, Galatians 6:7, Baltimore-style!

Fantastic essay. As a Royals fan, I often felt the 29-year playoff drought was due to some failing of mine. But since I’m still the same old degenerate I always was, I guess not…

Great essay, David. Also cool to know that you grew up in Silver Spring! My ears would prick up when I’d hear references to Montgomery County and Prince George’s County in The Wire. Sort of curious as to whether you feel any lasting connection to either of those places or identify more strongly with Baltimore now.

My goodness, David, you’re probably responsible for the sorrowful last act of Curt Flood. How better could the Lord punish a nascent champion of labor?

More work to do, I guess.

You cut me deep on that one.

Aw, you know I’m just joning on you.

Ha! What a great read. I’m a lapsed Catholic, and, when the sporting occasion takes me, a lapsed atheist too.