It’s hard to scale the heights of requiem without stumbling into a deep ravine of sentiment and cliche, and I know some will measure what follows against the known place of the old Baltimore Sun in the pantheon of American newspapering. No, we were not a Washington Post of the last late century, with Bradlee’s feet on the desk and Watergate dueling scars adorning a set jawline, or a New York Times for the Middle Atlantic, our paper-of-record certitude enshrining our every effort. We certainly weren’t some rough-and-tumble tabloid squealing about headless bodies in topless bars, or even a Chicago broadsheet or Hearst rag for which Hildy Johnsons might labor with gin on their breath and cigarette burns between their typing fingers.

We were pretty staid. Too staid, perhaps, and a little too proud of a noble, grey history. We were often accused by our younger sibling, the Evening Sun, of pretense and pomposity. H. L. Mencken, who we vaguely claimed but who had in fact labored for most of his career at the evening edition, remarked famously that the morning paper’s scribes wrote like accountants. Even when I arrived in 1982, there was still some of that. And yes, we puffed ourselves up with the idea that what we wrote mattered. The wall-sized photograph of the Baltimore skyline in the fifth-floor conference room was crowned by The Sun’s light-for-all masthead and underlined by the affirmation: “The Baltimore Sun. One of the world’s great newspapers.”

Evening Sun wags — and every last one, even the hacks who couldn’t write a lick, thought themselves a wag when compared to the morning paper’s Brooks Brothers-wearing, Washington-bureau-coveting pecksniffs — quickly fashioned a savage, get-over-yourselves reply: “The Evening Sun. One of the world’s newspapers.”

Having been hired straight out of college by The Sun, I might have done better, in the short run, to have landed at the evening paper, which held local coverage to be its bread and butter. By contrast, the morning staff was intensely hierarchical, and a boychild hired to be the junior cop reporter was staring at a couple years running the police districts, then a three- or four-year sojourn in a county bureau, then perhaps, an extra hand in Annapolis during the legislative session. If you jumped through all those hoops without falling on your ass, if you looked and dressed the part, and if you showed enough level-headed temperment to master The Sun demeanor, a Washington posting might just beckon. Or perhaps even one of the coveted foreign bureaus.

In previous decades, the newspaper had put a premium on Harvard men, and yes, there were a lot of bylines with waspish names, right down to the juniors and thirds, initials for given names and old family monikers lodged somewhere in the middle. There was, at the old Baltimore Sun, a certain code of employ. The place smelled of a certain gracious, dry rectitude, with just a slight trace of formaldehyde. I think I smelled of something else, something more common to ordinary newspapering.

But damn, I was proud to be there in my twenty-second year, and yes, I aspired to join that long grey line. And yet the guardians of the old Sun, while polite and even tolerant at points, could be intimidating. Nothing made the young metro-desk proles go slack-jawed faster than the vision of a Price or an O’Mara gliding through the newsroom on home leave from the Paris or Jerusalem bureaus. These were men who closed hotel bars in Beirut and Rome, who buttonholed world leaders, who strutted through coronations and shooting wars. And even more whispered and enigmatic was a newsroom visit by one of the kohaneem of the Sun’s inner temple, the editorial writers.

Mostly, these men — and for a long while they were mostly men, and very much white — would only deign to journey up from their fourth floor Holy of Holies and maneuver through the newsroom maze to consult with the National Desk or the Foreign Editor, or the top editors in their corner offices. There was nothing that a metro reporter could tell these gents about something as pedestrian as Baltimore, Maryland. The whole of the city was self-evident to these men, as were we who scurried through its political wards and police precincts.

I say this with no cynicism whatsoever. I was a kid then, and the resumes of these giants were speckled with the great postings of American journalism. They had seen great happenings at close hand. And they had written of real spectacle and history, the stuff of real purpose. Me, I was still waiting for the State Police barracks in Hagerstown to identify the second victim in that three-car fatal.

My favorite of the high priests was physically unprepossessing. In fact, he was elfin.

Theo “Ted” Lippman, Jr. was a man who I managed to pass in the hallways and corridors three or four times a week. He was never without a scrap or two of paper, always in mid-assemblage of a pithy column on politics or current events that ran to about 500-600 carefully chosen words and was lodged at corner left on the opinion page beneath the totem of staff editorials. I wrote it long, goes the old newsroom saw, because I didn’t have time to write it short. Lippman’s column was always so disciplined and tight, so keenly edited, that I imagined beads of blood forming on his forehead as he trimmed his way into ten or eleven column inches. He was always worth the read. Even more so when compared to many of the droning, this-bears-watching, yet-on-the-other-hand staff editorials perched atop his signed column.

Mr. Lippman was also an expert on the life and work of Mencken, the great essayist and skeptic who bestrode the joint Evening Sun-Morning Sun newsroom like a colossus. The Baltimore paper had not produced anyone as elemental to American culture and, though many had ceased to read Mencken as part of the literary canon, he remained the essential icon for those of us on Calvert Street. For one thing, Mencken could turn a phrase; his memoirs and essays are often brilliant and, at points, genuinely timeless. For another, we were all of us wandering the dim halls of an ancient ink-stained cloister, and such places demand at least one founding saint.

Ted Lippman’s editing of Mencken’s work, published several years before, marked him in my mind as more than one of the paper’s better political columnists. He was an Author, a man of letters capable of assessing and framing the legendary work of the Great Sage. That he had published other political biographies of Ed Muskie, Spiro Agnew and Franklin Roosevelt compounded my awe.

Moreover, Mr. Lippman’s knowledge of the American presidency seemed to be without peer. He could conjure trends and historical precedent in fresh ways, and his column became a veritable provocation of theory and argument in presidential election years. Before arriving at The Sun in 1965, he had been the Washington correspondent for the Atlanta Constitution, the great Southern citadel of progressive change in the civil rights years. He had covered the March on Washington and King’s great oratory at the Lincoln Monument. He had covered the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missle Crisis. Old Axe-Handle himself, Lester Maddox, had derided Ted Lippman in print and by name as one of the “pinks, punks and eggheads” who were so foolishly serving godless communism in advocating for social justice and integration.

When we passed in The Sun’s hallways or found ourselves sharing an elevator, Mr. Lippman would invariably nod, offer a quiet how-are-you and proceed past. Never do I recall having the effrontery to venture more than a “good column today” or some bland muttering about the weather. Mostly, I just smiled back and considered myself wanting in the eyes of one of the old Sun vanguard. Not that I could bear to say much more to O’Mara, or Price, or any of the priestly class; I was still unwashed and unpromoted, still running the police districts and gathering string on ghetto murders, still donning blue jeans and polo shirts, still unable to sustain myself for more than twenty minutes straight as an apostle of The Sun way. I was a reporter. I worked with reporters; we spilled soup and coffee on ourselves, wrote too long for the newshole and then had our last grafs trimmed away. This Lippman fellow — he was a journalist.

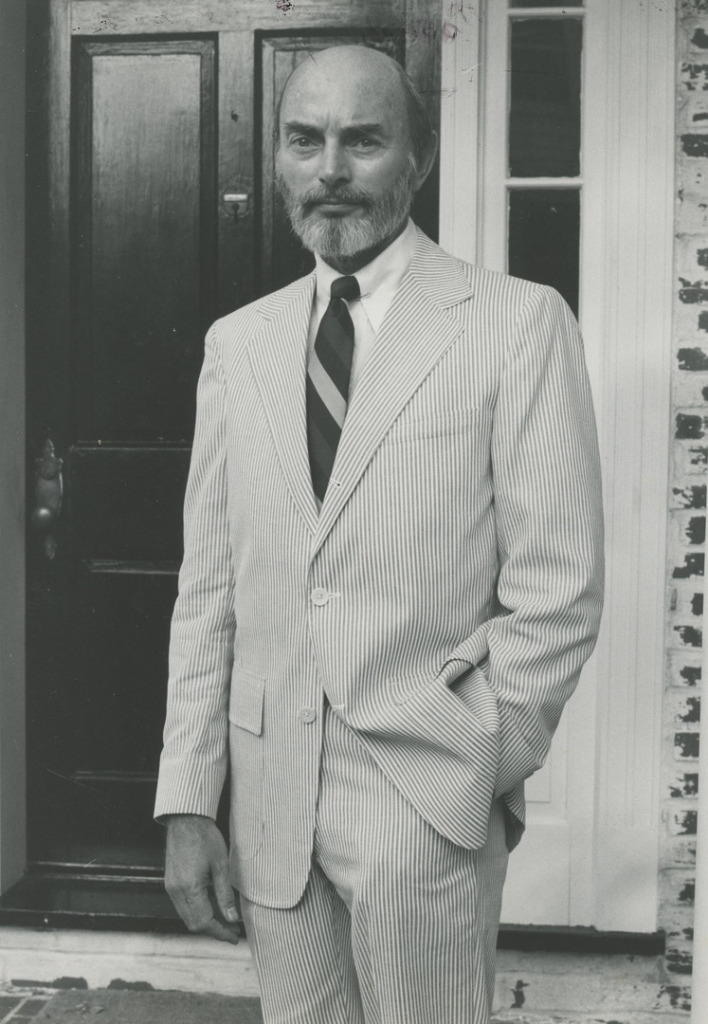

A Brunswick, Ga. native, he had a perfect, gentle drawl. He wore seersucker in the summer. And bow ties, for the love of Christ. That’s right: The man could come correct in a fucking bowtie, looking as if he was ready for either the Scopes trial or the Pettis Bridge. Watching him, I actually conjured an entire fictive backstory for the man: Lippman, Jewish name. Southern heritage, though. A great great grandfather who was one of the sutlers following Sherman’s army into Georgia, then settling to embrace life on a small town square. Maybe a dry goods store. Then a couple generations of gentle assimilation along Atlanta’s Peachtree Street, until finally, young Theodore rebels just enough to tell his father that the family business will have to do without him, that he is a man of letters. And eventually, he writes his way to the top tier, an advocate for a new South and a careful, thoughtful observer of real history. Not that I had the courage to inquire directly. As I said, I don’t think I ever formed any sentence longer than a basic greeting or compliment, but it was enough: The sight of Ted Lippman moving past me in a hallway made me proud to work at my newspaper.

His daughter got to Calvert Street about six years after me, hired off the San Antonio Light by the Evening Sun. She was a tall drink of water, too, seemingly towering in heels over her father in the rare moments when I saw them together. But don’t go there yet: She was married and so was I, and of course, she was Evening Sun. Our early interactions were spiced with the requisite amount of soft, familial snide that passed for inter-edition collegiality. The woman actually thought she worked for the better newspaper. Or at least, she carried it like that.

When the papers were merged and we were working on the same metro staff, I got to know her a bit better. I once spilled a coffee on her desk blotter and earned some playful wrath for it. I offered to buy a new blotter, she asked for a hardback copy of Homicide instead. When she published her first novel a few years later, I happily blurbed it. We did a bookstore signing together once in White Marsh. That sort of thing.

Years later, I was separated, out of a marriage. Her, too. Ignoring the fixed newsroom wisdom that for good of the human species, veteran reporters should never mate or reproduce, we began to date and, at some point, it was time to face the lady’s parents. The scenario, fraught enough under the usual circumstances, takes on added comedy when an ex-metro desk scribbler, and a cop reporter at that, shows up to claim the hand of the daughter of an old Sun sachem. On the Calvert Street of Ted Lippman’s day, an editorial writer and signature columnist wouldn’t wipe his ass with a police reporter, especially one as badly dressed and unevenly tempered as some we might name.

By then, both of us had left The Sun. I was among the youngest journalists taking a 1995 buyout offered by the newspaper chain that had purchased the paper; Ted Lippman was among the oldest. The fact that I had taken up with Laura after publishing a couple books helped my cause somewhat; the television work was, of course, tinged with apostasy. And even for as much of a progressive as Ted Lippman managed to be in his own era — his 1970s beard alone was enough to make his insurance-salesman father apoplectic at the idea of his son’s possible leftist allegiances — I’m sure I was a lot for him to swallow. Once, at a family gathering in a Baltimore restaurant, I made a remark about having been called a Marxist in print by someone. My father in law didn’t hesitate. “Well,” he asked, his face offering only bland curiosity, “are you a Marxist?”

It turned out the version I had fabricated of the Lippman family history had only small shards of truth. My wife’s great grandfather went to the southland a Jew, and was even a president of his Alabama temple. But his son got wise to his environs and reached adulthood as a Methodist, and the grandson, Ted Lippman, was so far removed from the sons of the covenant that he fairly broke out in a sweat at being confined to a synagogue for the exhausting, three-hour duration of my son’s bar mitzvah. Nonetheless, I spent my years as Ted’s son-in-law engaged in a prolonged effort to bring him back to the tribe, if only for comedy’s sake. Cinephiles will remember the running gag in Cat Ballou, in which Cat’s rancher-father is convinced that his Native American farmhand is, like all of his race, certain to be among the ten lost Israelite tribes. “Shalom,” he continually greets the kid, much to the farmhand’s annoyance.

As it was with me, arriving at my father-in-law’s Delaware shore home, taking a seat on the sofa and interrupting his perusal of the Sunday morning political talkfests with as much Yiddishism as I could cram into ordinary sentences. “Gevalt, what kind of narishkeit is this you’re listening to? Wolfowitz is a behaima. This whole thing with the weapons of mass destruction? Bupkis. So, nu, what else is on? You have the remote? Geviss.”

Alas, Ted Lippman never broke character. None of it stuck. Not a word.

His wit was dry, and always with that laconic Southern windup. It was not the call-and-response banter of the East Coast; his best lines would be carefully set up, much as in his columns. Once, when Laura was trying to prevail on him to order carry-in sushi with the rest of us, her father refrained from any single negative assertion with regard to the eating of raw fish and seaweed, merely conveying looks of increasing perplexity and dismay. And then finally, an hour later, eyes twinkling, as he opened the box flap of his dissenting order from Mancini’s:

“Pizza. Now this is American food.”

He was ever agreeable, unless either of his daughters wanted to argue with him, at which point he delighted in playing the provocateur. He would often back into outrageous statements and positions, then profess shock when Laura or Susan would go for the hook. Then he would reel them in with even more indefensible outrageousness. He consistently denied any childhood memories in which he was complicit or guilty in their eyes, insisting that he had no recollection of any such circumstance. When he let you know him, he was hilarious. And damned clever. And just as I was proud to work at his newspaper, I was proud to find myself in his family.

I tried to hug him a few times. Jews hug. We do it with relations that we love and we do it with those that we don’t much like, because, hey, with the ones you don’t like, a warm wrap-around puts the schlemiel to shame for whatever mishegas he’s done to annoy you in the first place. And, too, family is family. At any moment the Cossacks may ride into town and carry off one or two of us. So hug while you can.

I would throw an arm over Ted Lippman now and again because I loved him. And yeah, he would squirm a bit; Protestants aren’t adept at physical embrace, though to be fair, my mother-in-law, Madeline, took to it fine. But her husband? Cornered prey. Finally, on a morning of doorstep goodbyes, my sister-in-law broke everyone up:

“Well, if David’s going to hug Daddy, I suppose I’ll have to do it, too.”

And she did. After which her father looked on me as if I was turning his own children against him.

For fun, we debated politics. I would stake out a position to the left of the Democratic party and then fight from that fixed position against the encyclopedic knowledge of my father-in-law. By standards of my own argumentative family dialectic, it was gentle stuff. Mostly, we talked about The Sun, the newspaper’s struggles and the many buyouts that followed our own. We marked the departures, the forced retirements and finally the firings of so many people that we knew and cared about. There was no schadenfreude. Ted Lippman had been a Sun man in the halcyon era, when it meant something. And as a kid, I had at least been allowed a brief glimpse of the garden before the hissing snake of out-of-town ownership, the bite of the bad Wall Street apple, and the long fall from grace. In the last couple years, it pained me that I could offer less and less newsroom gossip to my father-in-law, or that what gossip I knew was about people too young to tickle his memories.

“Shame,” he would say, the single word sufficing for all that had happened to the newspaper.

He had tried to keep a hand in, to write a column or a book review now and again, to keep those muscles sharp. But it got so bad that at one point, the op-ed editors — on orders from Chicago — were no longer paying even nominal fees for columns and essays. And Ted Lippman was a professional, and no professional writes for free. When the paper was slow to pay for one of his last printed columns, my father-in-law, with Southern pride and patience, repeatedly called to inquire about the missing check. Finally, after months, he called the newspaper’s editor in chief directly:

“Tim? This is Ted Lippman I know now that you’re not going to pay me for the column, but I’m writing my memoir, and I’ve reached the exact place in the story where I need to know why you won’t pay me for the column.”

The check arrived a couple days later.

But he was a forgiving man, and if a fight ever wounded Ted Lippman, he never showed it. Not to me. He held no grudge against that editor slow to the petty cash drawer; in fact, the story of getting paid at last was worth more to him than the fee itself. The Lester Maddox column that railed against him stayed framed behind his desk for his whole career and into his retirement. Even the bosses with whom he had tangled at The Sun on matters of real significance were, in the end, benign colleagues when he spoke of them in memory.

As for me, the proto-Marxist, bear-hugging, television-hacking member of the rabbinate, I knew I was near enough to his heart when he gifted me all of his heavy clay poker chips and two decks of vintage playing cards featuring the high and mighty of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. These were touchstones of Herculean, late-night card contests featuring Price, O’Mara, Jenkins and the other grey legends, sacred relics rescued from a lost, fallen temple.

They are deeply prized. As was he.

- 391shares

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

Baltimore is better for the legacies of Theo and Laura Lippmann and David Simon. People who help us to look at ourselves, and think about how our communities came to be as they are,represent the best of the uniquely American social order. Theo’s knowledge of presidencies, and David’s depiction of our city in The Wire, give us context to assess our lot in this world. The family’s skill in provoking healthy thought is a blessing.

David, hello to you. I was surprised and saddened – but pleased in a way – to come across this just now. I just discovered your site and am enjoying it very much. About Ted, this was a beautiful description. I’d like to add a very small story for you and Laura (which you can post or not – up to you) because I’ve told it a hundred times over the years to others. It seems appropriate here, not because – as I tell others – it was the most mortifying moment of my journalism career, which it was, but because I use it to describe to others what it means to be a gentleman. Ted was indeed one of the high priests to whom I might have nodded, but little else, not being worthy of their attention whatsoever. So one night, as I was leaving and Ted was standing outside the lobby, I think waiting for a taxi, I said hello, we must have traded a couple sentences, I don’t remember, maybe his car was being repaired, and I offered to drive him home. He accepted. It was not until I opened the passenger car door that I realized I had perhaps two months of old newspapers strewn on the passenger-side floor, mixed in and around a dozen empty crushed coffee cups, many of which were filled with old wet cigarette butts, various empty coke bottles, empty bags of chips and food, and my ashtray was overflowing. I suddenly realized the entire old beaten-up Subaru reeked of cigarettes. And it was raining so it was impossible to put the windows down. I apologized briefly, hoping not to draw any more attention to this as possible as I began to throw things into the back seat. I’ll never forget how struck I was when this man, dressed that night, in fact, in seersucker and the bow tie you mentioned assured me quietly the car was fine, not to bother moving anything, slid in like he was taking a seat at a restaurant, looking perfectly comfortable, and thanked me for the ride. From there, it’s a blur. We drove north somewhere and all I remember from the ride is that he was graciously treating me like a colleague while I was sitting there incapable of thinking of any question to ask him – hardly the quality of a reporter who deserved the compliment. I have no memory of where we went or my drive home – only that feeling of being with greatness and horrified at my car. For various reasons, it is one of most enjoyable memories I have while at The Sun.

And while I’m visiting you here, I’ll let you know that, by the way, you have an enormous popularity here in Romania. The Wire still runs and many folks are huge fans of you personally. And I always delight in some personal way when I see some of Laura’s books in the local stores here, as I do. Bucharest in a funny way is often more American than America. So if you guys ever find yourself in the area, I’m sure you’d get a terrific reception. In the meantime, it is great to see Ethan and read up on your projects. All the best to you and Laura. Take care.

Beautiful tribute David.

Protestants should always be forced to hug.

Condolences from Australia to you and Laura.

I’m so sorry for your family’s loss. What a wonderful life he had and he even got some hugging which even those who protest secretly like. Really enjoyed getting know Ted through your remembrance. He was clearly a singular gentleman and a gift to those who know him.

A transplanted New Yorker currently residing in Brunswick,GA. In this photo he is the epitome of the gentile, southern sophisticate that you can still find hereabouts. May he find a cool shady spot on God’s veranda where the mint juleps are cold, tart and everflowing.

Your admiration and respect for Mr. Lippman shines through in every word of this piece, Mr. Simon. Thank you for allowing us to read it, and please accept my heartfelt condolences.

David, I am so sorry to hear this news. I felt your love and admiration for your father-in-law. Laura was blessed to have him. I hope you both cope well with his loss. Condolences and a Jewish hug. Helen

Beautiful.

May his memory be a blessing.

So sorry for your loss. Wonderful tribute. And the man definitely could wear sear sucker. You played your role well, keeping the relationship slightly off kilter throughout the years. Heartwarming and generous.

Very nice tribute to a wonderful man. But hey, did you ever catch me wearing Brooks Brothers? Or Rebecca? Or Will? Or Steve? Or Robert? Or Sandy? Probably Paul Banker was among the last holdouts, and looking back, if he wore Brooks Brothers, we should have as well. He, and TedLippman, stood for something.

Thank you for sharing these memories. My condolences to you and your family.

A terrific piece, David. It speaks not just about your lost father-in-law, but to something that all of us who toiled in the newspaper business have lost. My best to you and Laura, whose friendship remains one of the highlights of my years in the crime novel-writing trade.

May memories of the better times balm your sorrows.

Sorry for your loss. Sounds like the world lost a very decent man and a heck of a writer.

What a wonderful read – funny, as well as touching.

Men of his generation and his quality are to be admired; saying a lot with a little.

Condolences for you and your family.

A lovely remembrance. My condolences to you and your family.

Thanks for sharing this wonderful tribute.

Magnificent. Thank you for this introduction to a man any human being would have been privileged to know.

David, Thank you for this. It is difficult to convey the type of love that you and your father-in-law had for each other, but you did so, and did so wonderfully. My sympathies to your wife, to you, and to his family Mark

A beautiful tribute. My condolences to you and Ms. Lippman.

A wonderful piece of writing, David, and it captures the man and the institution. I came to work at the Sun 10 years before you did and left with the first buy-out in ’92, so I lived through all you described, knew all those people. Thanks for your insights and your eloquence. I’ll bet Ted was proud of you.

A beautiful piece. Mr. Simon, I am sure your father in law is smiling as he reads it.