A repost in honor of Father’s Day and the redoubtable Bernard Simon, gone these five years but I feel as if I am talking to him still. This was published in Lucky Peach #4 and while it is food writing, per se, it comes around to my father soon enough. Yeah, I back into it. But Dad, I miss you.

I want to embrace the best of the kitchen.

But if DNA is destiny, and genetics holds any sway at all over the human palate, then I have much—probably too much—to overcome.

The Simons come from peasant stock, and by that I don’t mean the countryside of Alsace or Tuscany or any other place where cuisine makes the days true and beautiful, where gardens and orchards and farms and village butchers conspire for a cuisine both purposeful and ingeniously simple. We are not the progeny of any agrarian ideal worthy of Impressionist paintings.

No, my father’s people were kicked-to-the-ground-by-Cossacks peasants, wandering Pale of Settlement Yids who lived with one or two bags always packed and spent the early moments of the last century running ahead of whatever Jew-hating militia was on whichever side of the Polish-Russian border. Like fodder for an Isaac Babel story, we hauled ass from pogrom to pogrom, dragging our huddled mass west until a sign said NEW JERSEY.

My mother’s people ran, too, first from the Hungarian countryside to Budapest, where my grandfather changed his name from Leibowitz to Ligety, stealing the latter from an Austro-Hungarian family of some repute, hoping to blend. Didn’t work, though—a Jew by any other name. So Armin Ligeti—the extra i was acquired at Ellis Island amid a rush of incoming Italian stock—kept running until he felt a bit more welcome in Williamsburg, and later, in the Bronx.

The story ends—and begins—with one grandfather a salesman for Breakstone Brothers Dairy, slinging butter and cream to mom-and-pop stores all over New York, and the other ensconced behind the counter of just such a store in Jersey City, selling pickles out of a barrel and borscht out of the jar.

Both households kept kosher. They had one foot on a new shore, but still trusted in the world of their fathers. They raised children amid a Great Depression, teaching them the value of a dollar and the notion that when it came to food, there could be nothing new or clever under the sun. This sensibility endured well into my youth.

“Your mother makes better,” was a credo of my childhood. We dined out infrequently and only on special occasions. There was a favorite Chinese dump. There was an Italian joint where we gathered once or twice a year. And then, when someone graduated or relatives came to town, there would be a rare pilgrimage to some grander palace of white tablecloths and wineglasses, with mine always promptly removed. Experimentation was at a minimum, so much so that once, when I was eight years old, I tried and failed to order raw oysters at a downtown restaurant. The Blue Points. A half dozen, please.

“Davy, they’re raw.”

“I know.”

“That means they’re not cooked.”

“Right.”

My father frowned. Who eats oysters? Who eats anything uncooked? Who goes to Duke Zeibert’s downtown, even on a special occasion, and pays these prices for food that no one even bothers to put on a stove? What mishegas.

My mother turned to reinstruct the waiter.

“He’ll have a shrimp cocktail.”

It wasn’t that we kept kosher—that wall had crumbled twenty years earlier, when my older brother, a notoriously reluctant eater, was treated to bacon by neighbors in a Brooklyn apartment house. As a two-year-old, Gary Simon took to craving pig as he craved no other sustenance, and finally he began putting on weight. Every dietary law in Leviticus was henceforth repealed.

But as a household, we were residually kosher. Shellfish was suspect, and aside from morning bacon, pork was never on the menu. More than that, exotic dishes—new cuisines, new ideas about food—were problematic if they took more than a half-step away from the known and fixed. My mother was an excellent cook, but almost all of what she served would have been recognizable and acceptable to her parents, if not her parents’ parents. Brisket, roast chicken, chopped liver, chicken soup: food was good and plentiful; it was not a mutlticultural adventure.

By the time I was born, my parents had moved to Maryland and the shores of that great protein factory, the Chesapeake Bay. Yet I did not taste a raw oyster until I was thirteen, or a raw clam until a year later. And, in my fifteenth year, I finally sat down with a knife and mallet and began breaking apart a dozen steamed blue crabs—and only then because my sister had taken a waitressing job in an area crab-house.

When I was in college, my parents offered to take me out to dinner one weekend. I chose a French bistro and ordered a plate of sweetbreads.

“Davy, do you know what sweetbreads are?”

“Sweet bread,” I deadpanned. “Something like a cinnamon roll, right?”

And my mother, not seeing tongue lumped in cheek, turned again to the waiter to rescue her youngest unschooled child from imminent and avoidable disaster.

* * *

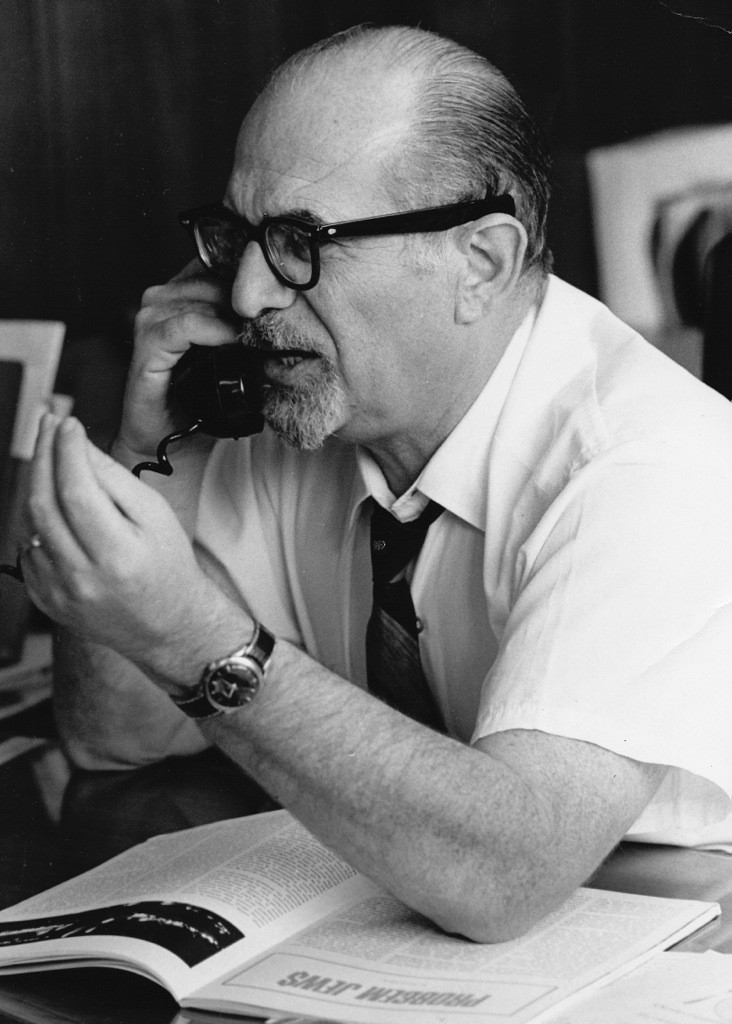

My father was all about salt, which is to say, he ate Jewish.

Matjes herring was better then Bismarck, but both were preferable to herring in any kind of cream sauce. The very idea of cutting the salted, pickled-without-pity taste with anything vaguely neutral or sweet was the mark of the apostate. To my father’s reckoning, a Jew caught dipping a piece of herring in cream might as well just slather mayo on fish sticks and crawl to the nearest baptismal font.

Pastrami, with the fattiest parts untrimmed, was lean corned beef perfected. The trick to great borscht? Salt that sucker down. The trick to great shav? Well, salt helps, but there is no such thing as great shav. A hot dog was a hot dog with brown mustard and boiled kraut. When my brother married a Wisconsin girl and brought her back to the family preserve, she punched a hole in the known universe by attempting to dress a Hebrew National dog with ketchup.

My father dryly threatened to notify the rabbinate and there was talk of a bet din, a religious court of inquiry. Spinoza, my father explained, had been excommunicated for less, merely because he greeted the Enlightenment by questioning the very idea of the Hebrews as Chosen.

“This is worse,” said Bernard Simon, intimating that absent an immediate repentance, a Biblical stoning might be regrettable but necessary.

In 1977, my father was downtown, working at the B’nai B’rith Headquarters in Washington. Armed members of a local Muslim sect, a breakaway from the Nation of Islam, seized the building along with other DC locations. As the day dragged on, a nearby Hilton hotel prepared sandwiches, which were brought in to feed the hostages. Sitting on the floor with nearly a hundred others, with a half-dozen armed men hovering, my father unwrapped the cellophane from a corned-beef sandwich to find that it was on white bread, and sullied even further by a schmear of glistening white mayonnaise. He turned to a coworker and said—and this is not mot d’escalier on my part, this is an actual quote:

“Sid, they’re trying to kill us.”

To my father’s tastes, cuisine was sodium and chloride and only one possible permutation of those elements. It was belly lox before nova. And if the Parkway deli down the block had lox wings—the fatty part of the salmon near the fin that somehow retained even more salt than the sliced stuff ever could—well, pick up a half dozen of those and we can nosh. No bagel. No cream cheese. No tomato. Why trifle with such blandishments? Just bear down on strips of heavily salted, fat-greased fish on a plate. Maybe some seltzer to wash it down.

This was my birthright, my inheritance.

In the summer months, my mother—having some sense of food groups in which brine did not feature—would often start a meal with fresh berries and cream. Not crème fraîche, mind you—that stuff was for Presbyterians. No, the berries were made to swim upstream in a fat dollop of Breakstone sour cream—my maternal grandfather asserting himself from beyond the grave. But in whatever total war was being waged against the sweeter side of my father’s tastebuds, even this concoction was too close to some sort of salt-neutral Switzerland.

As a countermove, my father invented his own appetizer. He went into the kitchen, pulled out a sharp knife and a jar of Ba-Tampte brand (“tasty” in Yiddish) half-sour kosher pickles. He chopped two pickles into small cubes, and then mixed them with sour cream: Jewish tzatziki. Except more bitter, and more better to his way of thinking.

(Before proceeding further with this tale, I have to pause to remark on the fact of my father entering a kitchen anywhere, grabbing a sharp implement and a food item, then rendering that item into a different form, mixing that element with a second substance, and serving it. It’s impossible for me to convey the singularity of this event, except to reference another childhood memory, one in which my mother went to New York to visit her mother and sisters for a week. I was subsequently taken to the Parkway Deli for seventeen successive meals.)

When I first sat at a dinner table and peered over my summer berries to see my father’s bowl of dissent, I could only respect the depths. I thought I had seen the besalted Hebrew cuisine in all possible forms. What, I asked my mother, is that called?

Pickles and cream.

As a ten-year-old in the suburban Washington of 1970, the phrase “what the fuck” was not entirely unknown to me. But somehow I managed to suppress my initial reaction.

“Dad, you’re gonna eat that?”

“It’s good. Try some.”

I picked up a spoon.

Cornichons et crème. À la Chef Bernard.

* * *

I found the wider world, or perhaps, the world found me.

And now, at fifty-one, I’ve been to Georgia on a fast train, as they say. Been to New York, Paris, London, Capetown, San Francisco, Napa, New Orleans. There have been meals, oh yes, there have been some meals.

The Bristol in Paris. Le Bernardin. The French Laundry. The River Café in Hammersmith. The Ivy in Soho. Momofuku. Gotham Grill. Tasting menus from Dufresne or Mina or Colicchio, omakases from New York sushi lords and Los Angeles sushi nazis and Nobus upon Nobus upon Nobus Next Door, wherever they are to be found.

And, too, I’ve had time enough to hunt down perfection without pretense, on back roads and back streets. A slice of Di Fara’s. A T-bone and tamales at Doe’s in Greenville. A burnt-end sandwich at Arthur Bryant’s. Pork ribs at Smitty’s in Lockhart, Texas. Fresh, soft tacos from La Super-Rica in Santa Barbara. Malva pudding at that joint on the road south of Capetown. Brisket from that no-name shack in Georgiana, Alabama. In New Orleans, I’ve tasted the chicken à la grande at Mosca’s four times in a single life. In Baltimore, I’ve stood at the Faidley’s bar with a crabcake platter at least twice a year for my entire adulthood. And thanks to this Bourdain fella, I’ve wandered a campground in Opelousas, Louisiana, and watched an entire living pig transformed into serving sizes, tasting all and loving all.

I don’t claim to know a damn thing about food—about why a dish works or why it doesn’t, about ingredients or seasonal menus or wine pairings. My credentials are akin to someone who likes to drive a beautiful car at high speeds but sees no point in opening the hood and looking inside. I know when something new explodes in my mouth and messes with my brain; I have no clue how it comes to be, and my incuriosity when it comes to the world of the kitchen is, at this point, just embarrassing.

But I do love a new taste, a new experience. I know what I don’t know and yet am content to put just about anything in my mouth on even a little bit of say-so. My father, as you can imagine, found this appalling.

First of all, some of the stuff I ate didn’t have enough salt. And some of it was from countries whose cuisine was unknown and uncertain in say, 1955, when the invention of food was largely complete and fixed. And, too, some of it was ridiculously expensive.

My father was a generous man, a liberal, charitable man. But he also knew what he knew, and he knew the value of a dollar. Walking my father into Le Bernardin or Nobu would have produced apoplexy. Money was only money to my father; he would not begrudge anyone their pleasures, their luxuries, their extra expenses. He hoarded hardback books, for example. Cheaper paperbacks brought him no pleasure at all. A book was worth whatever anyone asked for it. But food? How good, how unique could anything worth eating really be? For my father, a child of the Great Depression, high-end cuisine was all pomp and presentation, and, he feared, a great scam perpetrated on a public easily impressed and hungry for status.

I remember the first and last time Bernard Simon tasted sushi—a cuisine that should have appealed to a man who had embraced fish and salt as an essential combination for life.

“People pay for this?”

Or the time my LA agent took us out for brunch at Barney’s on Wilshire, where my father ordered lox and eggs, a deli staple. Alas, it came with crème fraîche and Osetra caviar and was priced accordingly.

“Your mother makes better.”

And the idea of journeying to find the perfect fried-oyster po’ boy or the perfect pizza slice? The miles-to-go-before-we-sleep hunt for the barbecue place that has no name, no phone? The whispered rumor of a food truck that’s killing it according to Chowhound?

To my father, the world had lost all sense.

In New Orleans with my parents, I once tried to drive out of the city, west to Houma, Louisiana and a little shack named A-Bear’s, a place said to be serving a fried-catfish sandwich that made even full-blooded Cajuns weep with gratitude.

“Dottie,” he grumbled to my mother, as we rolled down I-10 and the city skyline receded. “Don’t ever tell anyone we went to Houma, Louisiana to eat catfish for lunch.”

When I told him that catfish might actually be dinner, that we might first stop for lunch in Thibodeaux for boiled crawfish, he began to panic. He knew there was no hope of a delicatessen in such a wilderness. Reaching for his wallet, he pulled out a coupon for a run-of-the-mill Italian joint in downtown New Orleans, a place where, if he had to eat Italian, he could at least order his preferred dish: veal parmesan, without the cheese.

“You’ll get a good meal here,” he said, waving the coupon.

“Dad, did you ever eat there?”

“No, but I got a coupon. And Italian is Italian.”

He died two years ago. Toward the end, he was invalided and his world was limited to the meals my mother brought him at bedside. Tellingly, as he began to fail, he lost his taste for salt, for delicatessen, for all the heart-stopping glory of pastrami or lox wings or knockwurst and kraut. The bypass surgery years earlier certainly provoked some of the moderation, but something else was at play. In the end, he was eating less and less, and most of it very simple, very basic, very bland. He developed a sweet tooth, of all things. Ice cream became one of his few remaining favorites. Regardless, and to the very end, if my mother made it, it was better.

* * *

Two weeks ago, I found myself exhausted after a long day on a film set. My family was back home in Baltimore, and the house was empty. I’d been eating late meals all over New Orleans, and of course, as anyone familiar with Crescent-City cuisine is aware, a string of late New Orleans meals will kill a man dead.

Anything worth doing is worth overdoing down here, and the only way to survive the local fare, good as it is, is to retreat now and again to one’s own kitchen. A salad here, a broiled piece of chicken there, and maybe, just maybe, you come off a 120-day film shoot with a body weight that is moderately less than planetary. So I drove to Breaux Mart, the neighborhood grocery, just before it closed.

And there, in the deli section, I glimpsed a jar of kosher half-sours. Not Ba-Tampte, but close enough. In the dairy section, I found Breakstone sour cream. And late that night, alone in the City That Care Forgot, I sat down and ate something that my father, a man who knew what he knew, had invented.

The first spoonful threw me back to childhood, a Proustian moment of remembrance and joy and, yes, sudden grief. I sat there eating and crying, finally admitting to myself that, for all the great chefs and magnificent dishes and wondrous journeys toward a finer and newer meal, this was, for me, utterly perfect.

I had seconds.

* * *

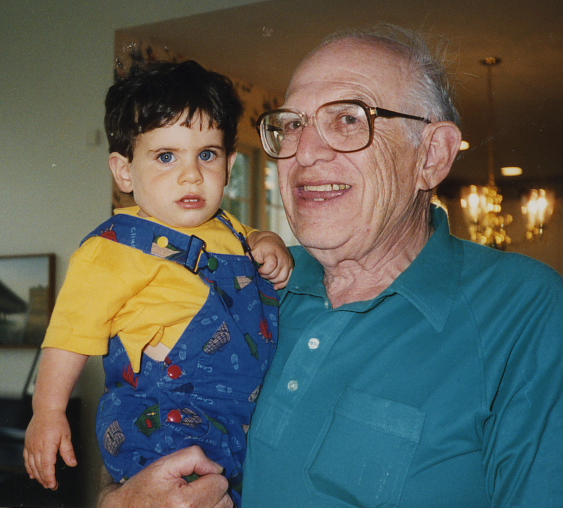

My father holding my son, Ethan. 1995.

- 72shares

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

Thanks for the repost, I hadn’t read the first time it was posted. Elegant writing yet as trim as your father’s preferred Pastrami.

“Residually kosher,” “…punched a hole in the known universe by attempting to dress a Hebrew National dog with ketchup,” “Sid, they’re trying to kill us,” “Bowl of dissent, I could only respect the depths.” So many wonderful gems in here David, also — regarding “Jewish tzatziki,” I always called the Raita (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raita) my dad made Paki tzatziki, heh.

I remember taking some sort of small issue in my stupidity with you years ago that you self-identified as a zionist. Reading this made me laugh and cry, just knowing how strongly the family lives between Muslims and Jews are so closely related. (My older brother was the first to break halaal, replace salt with cayenne pepper, my dad felt the same exact way about eating out, and had a wonderful sense of dry humor throughout his life, this really hit home for me.)

Your father was truly an extraordinary man and you’re undoubtedly a gifted writer. Thanks for everything.

P.S. Whole family is absolutely loving Show Me a Hero.

Yes, I believe in a Jewish state. And a Palestinian state alongside it.

And Netanyahu is nothing but a thorn.

You are right that people are more alike than we allow ourselves to believe.

Problem with a Jewish state is that a. it’s based on ethnicity (Zionism would prefer Jews over non-Jews; I’m with Ilan Pappé re:that 1948 was all about ethnic cleansing), which b. puts a preference of one ethnicity over another. Would a dispossessed Palestinian such as myself be able to live in Jaffa, amongst the orange groves? Not in a state that votes terrorists/fascists like Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir for PM, nor one that treats a baby burner (and murderer of three) in the West Bank by suspending a six month prison sentence. Though I would love to. The stories I hear of the land before the war break my heart.

Karim,

It is much too much to get into the dynamics of the Israeli-Palestinian question here, on a site where two people just shared a decent, cross-cultural moment that was absent the usual dumbass, one-sided and dishonest rhetoric. There is a right to self-determination for Jews and Palestinians that must be honored and achieved and all of the assoles who can only see one side of that equation — and not the other — are useless as fuck. They are not merely part of the problem. At this point, they are the problem.

If you want heartbreaking stories, they can be found on all sides of this unyielding conflict. As well as bad behavior and dishonor on both sides. And your unwillingness to leave even this small moment of connection alone — without injecting a full dose of self-righteous shitheadedness — speaks volumes.

I miss my father and my family’s culinary traditions. Writing about such, it spoke directly to someone who was from the other tribe. My man Yusuf replied with warmth and his own remembrance.

That was a simple, delicate, human good. Leave it to you to rush in at the first opportunity to fuck it up.

I’m sorry. I commented below (under my nickname, Kroms) how I loved this story.

Please feel free to delete the comment. I wasn’t thinking, posting during a moment of calm halfway through a long, bad day, though that is no excuse.

“People pay for this?” Oh my god, that line is genius!!!!!!! “Pickles and cream” is number two!

The extreme “warmth” in this and the way it’s written, had me in a fixed, gentle smile throughout. Beautiful and comforting…

This was wonderful. I’m watching my parents do something similar with Arabic/Levantine food. Feel like I could relate a book’s worth of eccentricities, a whole chapter for dad’s musings on freekeh soup alone.

Should you ever need a ba-Tempte fix, Wegmans in Germantown, Md., has a good selection.

For what its worth, I have yet to find a decent deli in Montgomery County, or, for that matter, in

the entire Washington Metro area. No one has ever heard of belly lox, although the nova at

Trader Joe’s is acceptable. Barely.

Reading this made me laugh, and nod my head, remembering Brooklyn cuisine. When we went out to eat, it was to Dubrow’s, a cafeteria on the corner of East 16th and Kings Highway. You would get a ticket from a dispensing machine that made a glorious mechanical ca-ching. Then the tray, napkins, silverware (real silverware, no plastic), and you got on line to be served whatever was on the steam warmers. I never got to do that, though. I was unceremoniously plopped at a table with my sister while the grownups got the food. I would have been trampled on that line. I ate off my parents’ plates. No tickets for little kids. The food was overcooked and bland, but Mom got the night off, and she always said, she’d eat anything as long as she didn’t have to cook it.

On special occasions, it was the Chinese place around the corner for chow mein and sweet tea, and maybe vanilla ice cream for dessert.

Obviously, Dad was easy to please. He was happiest eating apples. He would have one in each hand and one in each pocket. He loved Thanksgiving dinner, and my pot roast. In the years before he died, food became his primary pleasure. He had a neurological disease that caused him to fall backwards. When finally my mother gave up trying to care for him, he went from the hospital to a nursing home for rehab, he thought. He died of congestive heart failure the next morning. The staff at the nursing home told me that he had thoroughly enjoyed his dinner and breakfast; not even heart failure affected his appetite.

What a guy. I miss him.

And I suspect you will never stop talking to your father. I talk to my mom most days. When my girlfriend, who had always been told that her mother had breast cancer, was surprised to learn otherwise upon having to fight the beast herself, she said and I quote “I’m not talking to you now.”

Ann had been gone maybe 15 years. My father had been their family doctor when Marci was a child. He looked sheepishly at me, as if breaking a confidence, and said Ann never had cancer. She had a double mastecomy but mastitis, not cancer.Still a fearful thing in the 50’s. This was perhaps 2004.

They hover, I believe. All those loved ones.

Aw, I’ve been gone from Austin too long to have read this and not start thinking about my calendar and when I can hop a flight to a distended gut.

I’m put in mind of the teenage summer in the 80s I spent repairing air conditioners around DC (as you know 95+ degrees, 95% humidity, no AC in our truck, everywhere you go of course the AC doesn’t work and your first question was usually “where’s the attic” so that you could go crawl around where it was 120 degrees). But the perk was that the guy I was working for did AC work for the Omega, and we would ride by and get free lunch about once a week. Definitely the best part of the job.

Great writing.

I have a recipe for corned beef my mother gave me, who got it from her mother, who got it from a Jewish lady who lived down the hall from her in an apartment building in Newark, New Jersey, back in the 1940’s. And who knows how long it was in that lady’s family. This recipe is probably two hundred years old.

I haven’t made it yet. I’m not a very good cook. I had my mother give me all of her recipes, mostly for all the Italian staples: stuffed artichokes, broccoli rabe, pasta e fagioli, etc., so my girlfriend can learn how to cook them, but she can’t cook, either. And she’s ethnically Italian! I hate to say it, but generally speaking, American women under the age of thirty can’t cook for shit. I mean they can’t cook at all, these girls can’t even scramble an egg. They didn’t grow up in the kitchen like their mothers and grandmothers did. What the fuck is the world coming to when an Italian girl can’t cook? We are living in very dark times, I tell ya. I fear for future generations.

My Dad died on my 50th birthday. Gone 10 years now. Loved this piece more the second time around.

An excellent piece that took some steps down Memory Road.

Thanks for sharing.

We still have that debate over coffee awaiting.

I love this essay. Loved it the first time. Love it now.

It’s like having a seat at your family table.

Thank you for sharing this again.

Laughed out loud at “bowl of dissent.” Cuisine as identity.

With my dad it’s sliced tenderloin on dollar rolls with mayo and a little pepper.

Beautiful piece.

What a lovely read, suddenly I’m starving.

David. When writer’s fathers die, we talk to them forever after.

Thanks for this.

That was a beautiful tribute to your father. Your father would have loved the cuisine of Montreal, Quebec. The smoked meat sandwiches at Schwartz’s Deli may be North America’s finest sandwich and the bagels in Montreal put anything in New York to shame. In fact, a friend of mine opened a Montreal-style bagel and smoked meat shop in Brooklyn and they’ve become the talk of the neighborhood.

He went to old Dunn’s, I know. My father could find a decent deli on Okinawa.

Smitty’s in Lockhart. I love this post. My mother-in-law was so similar. She grew up in Colombia, S.A. One of eleven children. Their father was a coffee farmer. The only guy with any real money in town was Carlos Lehder. She hated eating out. With her, it was, “I can cook better.” We took her out to a fancy restaurant in Austin a few years ago, and she was visibly aggitated to have people waiting on us. She couldn’t believe we were wasting our money. Something to be said for that generation. Hard workers. Frugal. Careful. Love the stories and pictures of your dad. It is hard to lose the people who really love us. I miss my dad something fierce.

Also partial to Franklin on 11th and, in a pinch, the Salt Lick.

My barbecue wanderings across this hard land of ours have been both prodigal and purposed.

Franklin’s on 11th? Did you wait in line for three hours? I guess I’ve thought no barbecue is that good, but maybe the lines are shorter now that it’s summer and 110 degrees outside!

I did wait. I can be very Buddhist when good food is involved.